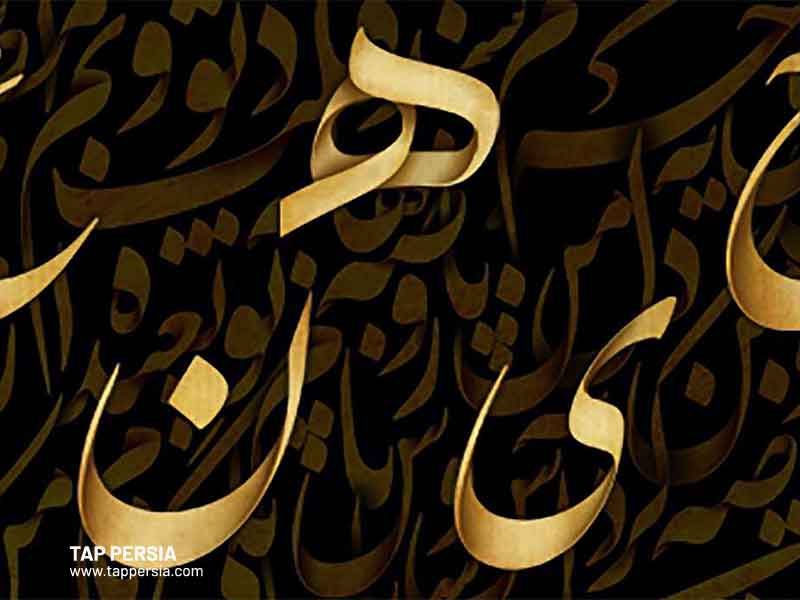

Persian calligraphy developed over time in Iran and the nations that depended on it or were influenced by it, such as those in Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the Indian subcontinent. Iranians were primarily responsible for the Islamic world’s transition of everyday writing into beautiful calligraphy, but throughout the time they also developed their own calligraphic techniques and styles. Despite having supporters in other Islamic nations, these inventive techniques and scripts are mostly associated with Iran and its spheres of influence, including Central Asian nations, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and India.

The Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage’s 16th session saw the registration of the Iranian calligraphy case, “National Program for the Protection of the Traditional Art of Calligraphy in Iran.”

History of Persian Calligraphy

Following Islam’s conquest, calligraphy was used as a writing style in Iran. Numerous Qur’an manuscripts were produced thanks to Abu Bakr bin Saad Zangi’s assistance in the city of Fars. Due to Chinese art’s influence and the Mongols’ authority, the gilded pages of books were initially ornamented with patterns during the reign of the Ilkhanids. Iranian calligraphy and handwriting became especially valued throughout the Timurid era.

The Nastaliq calligraphy, which was progressively developed from the blending of written and suspended calligraphy, was reinforced by Mir Ali Tabrizi. According to reports, Prince Baisanqar Mirza was the most well-known Quran calligraphy at this time. Persian calligraphy styles and typefaces were mostly created and utilized for non-religious materials including divan poetry, delicate artwork, and business letters. This is true despite the fact that calligraphy was more of religious and spiritual practice among Ottoman Arabs and Turks. Contrary to Iranian calligraphers, they also employ pens for secretarial and non-religious purposes, although the third line and copying and writing the Quran and hadiths show their artistic prowess at its height.

Those who are currently interested in the calligraphic arts, especially Persian Calligraphy, can attend programs offered by the Iran Calligraphers Association or take private lessons from instructors who specialize in this subject. You must go to the association’s local offices in order to enroll in the classes offered by the Iran Calligraphers Association.

Taliq Script

One may say that the Taliq was the first Iranian writing line in Persian calligraphy. The trestle, also known as the Taliq script, first appeared in the early 7th century and was used for nearly 100 years before progressively losing favor and its previous profitability. The lines of Nashq and Reqa’ were combined to produce the suspension, and Khajeh Taj Salmani was the one to legitimize this line. Khajeh Abdulhai Monshi Estarabadi later provided him with more guidelines. The Taliq features several circles, round letters, and many capacities for displaying different combinations and compositions. It is mostly used as a script for writing letters and official documents. Because of this, it is more well-liked by those who have a high degree of reading and calligraphic proficiency. Because people dislike the bother, it is not frequently employed in these tiresome times in terms of readability. As a result, this kind of lettering progressively declined in popularity.

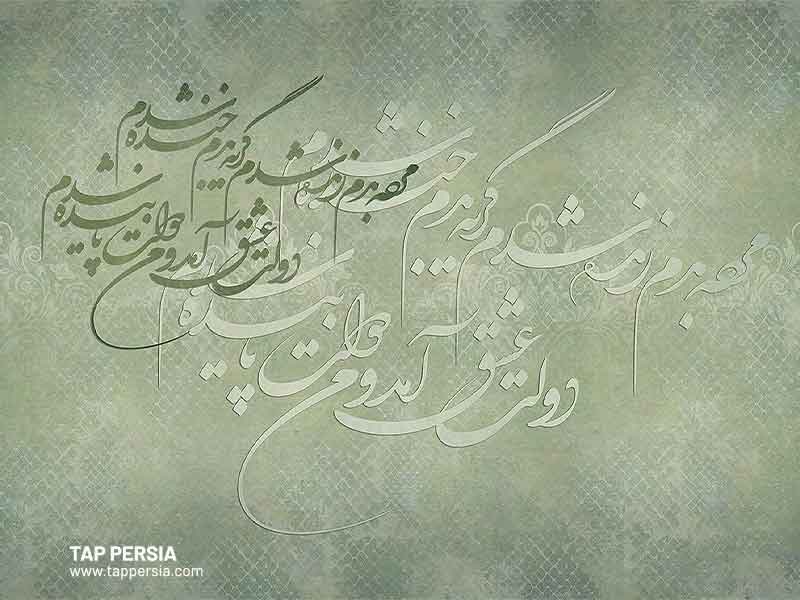

Nastaliq Script

Taliq inspired the creation of Nastaliq, which is the glory of Iranian ar

. The Nastaliq script, often known as “the bride of Islamic scripts,” is considered to be the most beautiful script among Arabic and Persian calligraphy and to be superior to the Islamic scripts. A new line, first known as Nashtaliq but later altered to Nastaliq owing to its frequent use, was eventually formed from the combining and merging of the two lines of Naskh and Taliq. Mir Ali Tabrizi (died: 850 AH) approved this line and suggested it as a rival to the previous six lines in the eighth century A.H. This line gained a lot of traction and significantly altered the practice of calligraphy.

The Nastaliq script developed and advanced greatly in Greater Khorasan, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and notably among the calligraphers of the Gurkanian court of India, in addition to those who resided in the region of modern-day Iran (who had a special connection to Iranian culture). The Hijri 9th–11th century may generally be regarded as magnificent centuries for the practice of calligraphy.

Nastaliq Cursive Script

Broken Nastaliq, the third pure Iranian script among Persian Calligraphy, was created in the middle of the 11th century Hijri. The governor of Herat, Morteza Qoli Khan Shamlu, was one of those who contributed significantly to the formation and stability of this new line. Its development may be attributed to the requirement for swift and straightforward writing in secretarial matters and, more importantly, to Iranian artistic taste and originality. Iranians developed the Taliq script as a result of the speed at which they could write, just as they did when the Taliq script first appeared. The Taliq script and the graceful script are combined to create the gorgeous Nastaliq script, which takes a lot of effort and accuracy to write. Nastaliq was created to have both speed and beauty.

Mohammad Shafi Heravi Hosseini Herati improved Nastaliq cursive, and Abdul Majid Taleghani set new guidelines and took it to its pinnacle. The Nastaliq Cursive script was improved upon by the Dervish Abd al-Majid to the same degree that Mir Emad had before in Nastaliq. After him, two more excellent cursive authors who significantly contributed to the promotion of cursive are Seyyed Ali Akbar Golestaneh and Mirza Gholamreza Esfahani.

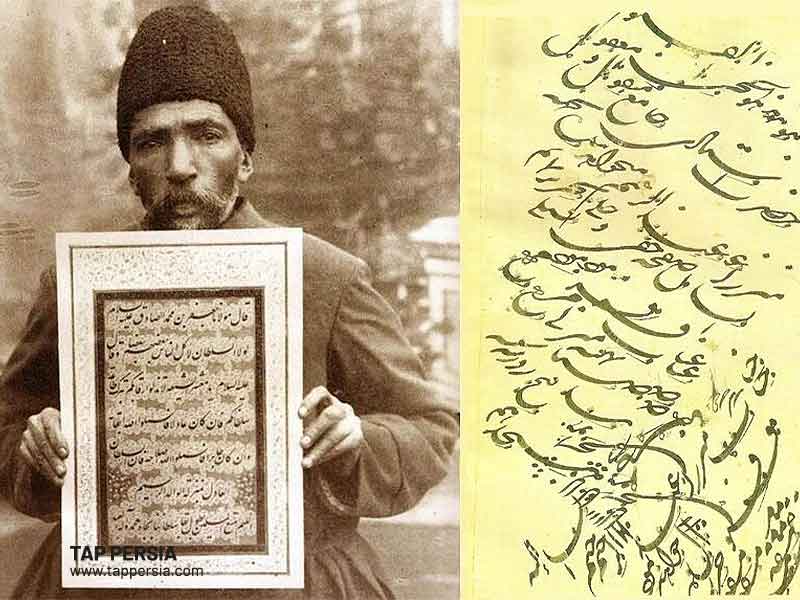

Qajar era

Changes were made during the Qajar era as a result of the introduction of printing and lithography, as well as the breakdown of the link between calligraphers and the previous masters of Iranian calligraphy, particularly Nastaliq writing. Siyah Mashq writing, commonly known as “Black Writing,” first appeared as a new language and form of expression starting in the 11th century of the Hijri calendar. It peaked in the 13th century. A language that has persisted today as a pure art form, unconcerned with the textual transfer of thoughts and focused entirely on producing aesthetic beauty.

The heights of this art were achieved during the Qajar era by masters like Mirza Gholamreza Isfahani and Mirhossein Khoshnevis. Due to the increased requirements of a society that was beginning to progress towards modernization at the conclusion of the Qajar era. Along with these advancements, calligraphy moved toward the applied arts.

Persian calligraphy adopted a new style in the 20th century by moving away from its primary purpose of writing and adapting to the demands of contemporary life. The Qajar and Pahlavi eras in Iran saw technological, political, social, and artistic advancements that served as the foundation for several improvements in the line. Writing and copying written works ceased to be the primary function of Persian calligraphy during the Qajar era with the advent of newspapers and periodicals. As a result, the line began to show more creative elements as well as personal and meticulous approaches, ushering in a new age with the spread of “Black Writings.” After that, during the Pahlavi era, he had to adapt to new social demands brought on by commerce, advertising, technology, and the advent of the calligraphic art form all over the world.

Ghazni Script

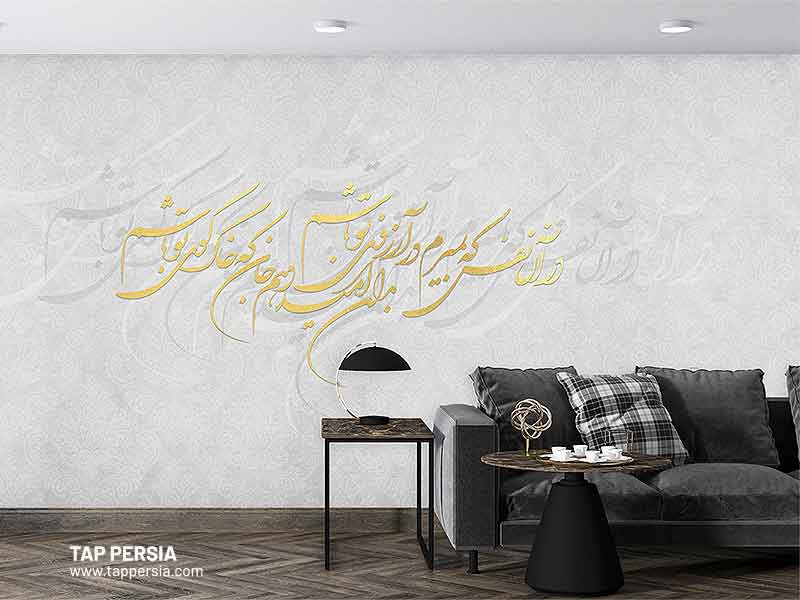

Along with other areas of art that saw substantial change in the modern age, Persian calligraphy too underwent modifications. Even now, we continue to see advances in calligraphy, both in terms of how it is combined with other arts and how it is presented. The Pahlavi era was characterized by connections to international contemporary art movements and bold pursuit of artistic innovation. We may use the calligram technique, which steadily gained popularity in the 1940s, as an illustration. Today, Calligram enjoys a unique position among art enthusiasts. Some calligraphy examples are derived from calligraphy’s roots, while others are the forerunners of contemporary Iranian painting styles. It can no longer be considered calligraphy or painting in these pieces since it has been so thoroughly infused with color and design. In this form of painting, the artist is free to create and design new shapes and color combinations, which helps him more easily realize his goals.

After the revolution, there was a dramatic increase in the demand for missionaries, particularly in the cultural field. Persian Calligraphy suddenly became popular among young people, and it once again became a staple of the visual arts. Numerous wonderful books and articles about this unique art were written as thousands of enthusiastic pupils investigated all its facets. The development of Persian calligraphy both quantitatively and qualitatively over the past three or four decades has been exceptional, to say the least. After the revolution’s first fervor, Iranian calligraphy is now reaching its maturity.

The calligraphy capital of Iran

The city of Qazvin has been dubbed the “calligraphy capital of Iran” by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance and the High Council for Cultural Affairs due to the cultivation of Persian calligraphers there, including Mir Emad Hosni (the great master of Nastaliq calligraphy), Mirza Mohammad Ali Khiarji Qazvini (the first calligrapher who drew Bismillah in the form of a Togra chicken). In addition to the permanent Qazvin calligraphy museum housed in the Chehlsetun Palace in Qazvin, significant Persian calligraphy events are conducted annually, including the biannual Iranian calligraphy festival, the Quranic verse calligraphy festival, the Ghadir calligraphy festival, etc.

Calligraphy and Handwriting in Iran Today

Generally speaking, the regular handwriting in Islamic nations has been influenced by the scripts created, developed, and perfected by Iranian calligraphers throughout the years. Every country’s educational system may take a different tack when it comes to the writing of schoolbooks, not always strictly sticking to calligraphic conventions and occasionally combining one or two scripts to aid in reading and comprehension. The Kitabi style, which was originally influenced by Naskh letters, was traditionally employed in Iranian novels. However, the hanging script of Nastaliq has started to take its place in recent years in student textbooks, and as a result, people today are more familiar with this script.

However, Iranians who have studied Nastaliq techniques in private institutions, as many have, frequently try to follow the fundamental principles of this style and particularly The Nastaliq Cursive script as a faster alternative in their daily handwriting—so familiarity with these various calligraphic styles is not necessary. Nowadays, everyday handwriting does not always follow these trends and instead reflects a personal preference or approach.

Iran Calligraphers Association

With the help of Seyed Hossein Mirkhani, Ali Akbar Kaveh, Ebrahim Bouzri, Seyed Hassan Mirkhani, Dr. Mehdi Bayani, a researcher and university professor, and others—and with the support of the Ministry of Culture and Arts at the time of its founding and launch—this association, known as the free classes of calligraphy(Persian culture)since 1329, was created.

On September 19, 1346, the Iranian Calligraphers Association obtained its formal foundation letter, and it carried on with its operations. After the Iranian revolution (1357), he gradually had a time of wealth and development, and at the start of his third decade, he began to practice Persian calligraphy, which is still practiced to some level now. The Iranian Calligraphers’ Association has several chapters in most major and minor Iranian cities as well as in a few foreign nations, and it has taught a large number of pupils.

Comment (0)