| Period | Founder | Length of Dynasty |

|---|---|---|

| Achaemenid Empire | Cyrus the Great | 550–330 BC |

| Sassanid Empire | Ardashir I | 224–651 AD |

| Samanid Dynasty | Saman Khuda | 819–999 AD |

| Seljuk Empire | Tughril | 1037–1194 AD |

| Ilkhanate | Hulagu Khan | 1256–1335 AD |

| Timurid Empire | Timur | 1370–1507 AD |

| Safavid Empire | Shah Ismail I | 1501–1736 AD |

| Qajar Dynasty | Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar | 1789–1925 AD |

| Pahlavi Dynasty | Reza Shah | 1925–1979 AD |

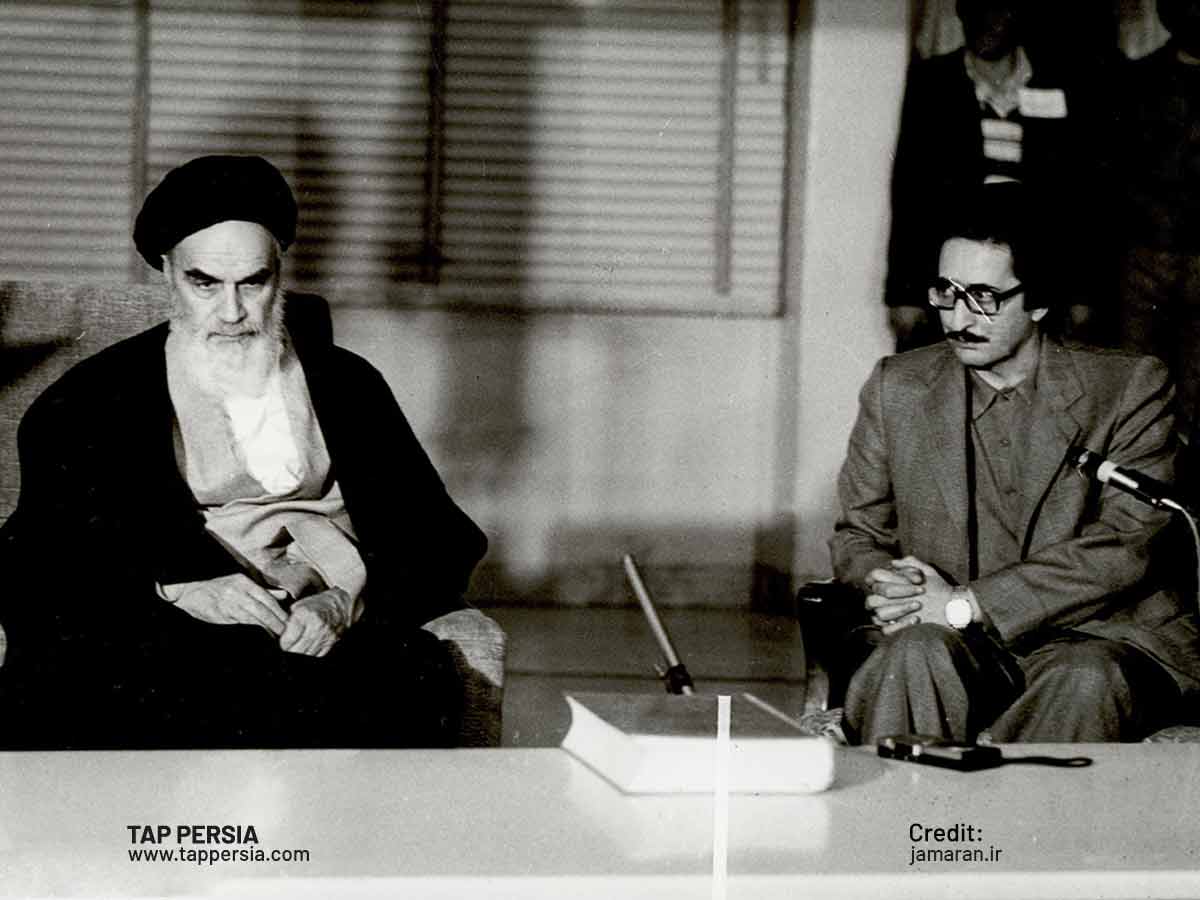

| Islamic Republic | Ruhollah Khomeini | 1979–Present |

With a long and interesting past that goes back over seven thousand years, Iran is one of the most ancient civilizations that has been in existence continuously. Ancient ruins throughout the nation provide a window into the illustrious history of the Persian Empire and its several dynasties. Iran’s archaeological monuments, which include everything from ancient towns to imposing palaces and revered temples, provide an unrivaled opportunity to delve into the nation’s rich past and Persian culture. Here, we’ll discuss the fascinating history of Iran as well as its different dynasties.

Ancient Persia: Cradle of Civilization

Iran has long been considered the cradle of civilization, and there is undoubtedly merit to this claim. It results from the amazing empires that ruled during Iran’s illustrious history. Many significant contributions conducted by the Ancient Persians helped shape the civilization we know today. The ancient history of Iran will now be discussed, along with the mysteries that have been discovered and understood thus far:

Prehistoric Iran: Unveiling the Origins

Iran’s early history may be split into three sections:

Prehistory

Iran’s prehistoric period is largely documented through archaeological artifacts, with early excavations occurring only at a few select locations. The study of prehistoric Iran has undergone a revolution since 1950 because of the resurgence of Iranian archaeology following World War II. The historian is still depending on archaeological data during the proto-historic period, although textual sources provide a lot of information. While some sources are local but not current, such as conventional Iranian folklore and tales that purport to describe events in the early first millennium BC, others are local but not contemporary. Some are useful in recreating events from the proto-historic period even if they are neither local nor current.

Paleolithic (ca. 100,000-10,000B.C.E)

An enigmatic surface discovery in the Baktaran Valley provides proof that humans have lived on the Iranian Plateau from the Lower Palaeolithic period. Deposits from a number of excavated cave and rock shelter sites, mostly in western Iran’s Zagros Mountains, date to the Middle Palaeolithic or Mousterian period (about 100,000 BC), and they include the earliest established proof of human settlement. In contrast to the clearly identified Middle Palaeolithic businesses recognized elsewhere in the Middle East, the Mousterian flint-tool industry discovered there is distinguished by the lack of the Levallois technique of flint chipping.

Locally, the Upper Palaeolithic Baradostian flint industry comes after the Mousterian. Radiocarbon dating indicates that it may have begun as early as 36,000 BC, making it one of the earliest Upper Palaeolithic structures in the history of Iran. It’s possible that the Baradostian was superseded by a regional Upper Palaeolithic industry termed the Zarzi following some type of cultural and typological gap.

The Mesolithic (ca. 10,000-5500 B.C.E)

One of the first regions in the Old World to undergo the Neolithic revolution was the Middle East. The establishment of settled village agriculture throughout this revolution was strongly grounded on the domestication of both plants and animals. Iran has produced a wealth of information on the past of these significant events.

Important western Iranian sites including Guran, Asiab, Ali Kosh and Ganj-e Dareh provide evidence of substantial changes in tool production, settlement patterns, and sustenance practices throughout the early Mesolithic, including the shaky origins of domestication of animals as well as plants. These community agricultural practices had spread widely by around 6,000 BC over most of the Iranian Plateau and low-lying Khuzestan. Tepe Sialk I on the edge of the central salt desert, Hajji Firuz in Azerbaijan, Tepe Sabz in Khuzestan, Tepe Yahya VI C-E in the southeast and Godin Tepe VII in northern Luristan have all shown evidence of rather advanced agricultural systems.

Elamite Kingdom: Ancient Civilizations in the Iranian Plateau

A civilization known as Elam lived in the area that is now southwest Iran. Elam was centered in modern-day Iran’s extreme west and southwest, extending from the Khuzestan and Ilam Province lowlands as well as a tiny portion of southern Iraq.

Elam, which is nearby Mesopotamia to the east, took part in the Chalcolithic period’s early urbanization. Similar to Mesopotamian history, writing began to appear approximately 3000 BC. During the Old Elamite period (Middle Bronze Age), Elam was made up of kingdoms on the Iranian plateau, with Anshan serving as their capital. Elam was based in the Khuzestan lowlands, with Susa serving as its capital, beginning about halfway through the 2nd millennium BC. Particularly under the Achaemenid dynasty that followed, when the Elamite language continued to be one of those in use in official settings, its culture was essential to the Gutian Empire.

Elamite appears to be a linguistic isolation, similar to Sumerian, with no known relationships to any other languages.

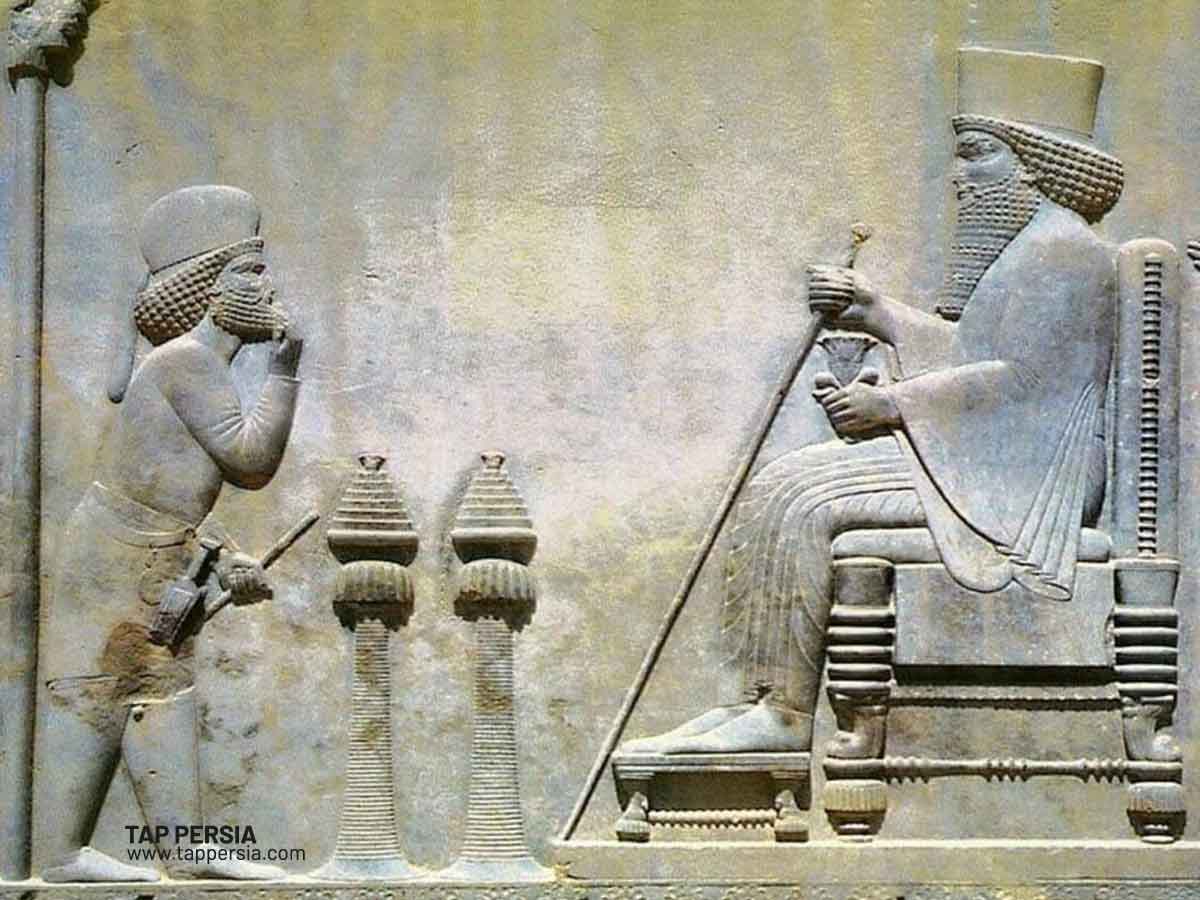

Achaemenid Empire: The Rise and Legacy of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus the Great established the ancient Iranian empire known as the Achaemenid Empire, sometimes known as the Achaemenian Empire, in 550 BC. It is one of the most important eras in the history of Iran. With a territory of 5.5 million square kilometers (2.1 million square miles), it was the greatest empire the world had ever seen, extending from Egypt and the Balkans in the west to Indus Valley and Central Asia the in the east. It was honored for its effective example of centralized bureaucratic administration, multicultural policies, construction of intricate infrastructure, adoption of official languages throughout all of its regions, and growth of civil services.

Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Achaemenid Empire in 330 BC was a significant victory in the Macedonian Empire’s continuing battle at the time. The vast majority of the territory once inhabited by the former Achaemenid Empire was controlled by the Ptolemaic Kingdom and the Seleucid Empire, which were both which were created as the Macedonian Empire’s predecessors following the Partition of Triparadisus in 321 BC. The Hellenistic era officially began with Alexander’s death. Hellenistic dominion endured for over a century previous to the Iranian aristocrats of the central plains regaining power during the Parthian Empire.

Parthian Empire: The Confluence of East and West

From 247 BC until 224 AD, the Parthian Empire, otherwise known as the Arsacid Empire, greatly ruled Iran and contributed to Iranian culture and politics. The tribe’s progenitor, Arsaces I, guided the Parni tribe in capturing the northeastern Iranian province of Parthia. Mithridates I expanded the borders by taking Media and Mesopotamia back from the Seleucids.

The Parthian Empire reached as far as modern-day Afghanistan and western Pakistan at its height, from the Euphrates’ northern reaches in what is now central-eastern Turkey. The Greek civilization that had developed in Iran throughout the Seleucid era was highly regarded by the Parthians, and several Parthian rulers were knowledgeable about Greek literature. The religious parliament and the noble parliament of the Zoroastrian priests made up the parliament Mahestan, which was made up of two parliaments.

Sassanid Empire: Maintaining Zoroastrianism and Persian Identity

The Sasanian Empire was the last Iranian empire in the history of Iran to exist before the first Muslim incursions in the seventh and eighth centuries AD. Ardashir I, an Iranian emperor who came to power after Parthia waned as a result of internal instability and battles with the Romans, built it. In 224 AD, he overthrew Artabanus IV, the final Parthian shahanshah, at the Battle of Hormozdgan, establishing the dynasty. He then set out to revive the Achaemenid Empire’s tradition by enlarging Iran’s realm.

At its height, the Sasanian Empire included the entirety of modern-day Iran and Iraq and extended from the eastern Mediterranean to sections of modern-day Pakistan, as well as from southern Arabia to Central Asia and the Caucasus. The Derafsh Kaviani was said to be the vexilloid of the Sasanian Empire.

Medieval Iran: Shaping the Islamic Golden Age

Find out what life looked like in Iran during the 7th-century Arab Muslim conquest. Investigate the sweeping changes in culture and religion to discover how Iranians managed to retain their identity, endure and exert cultural and linguistic dominance over the Muslim empire’s eastern regions. Continue reading to see how Iranians lived throughout this era of the history of Iran.

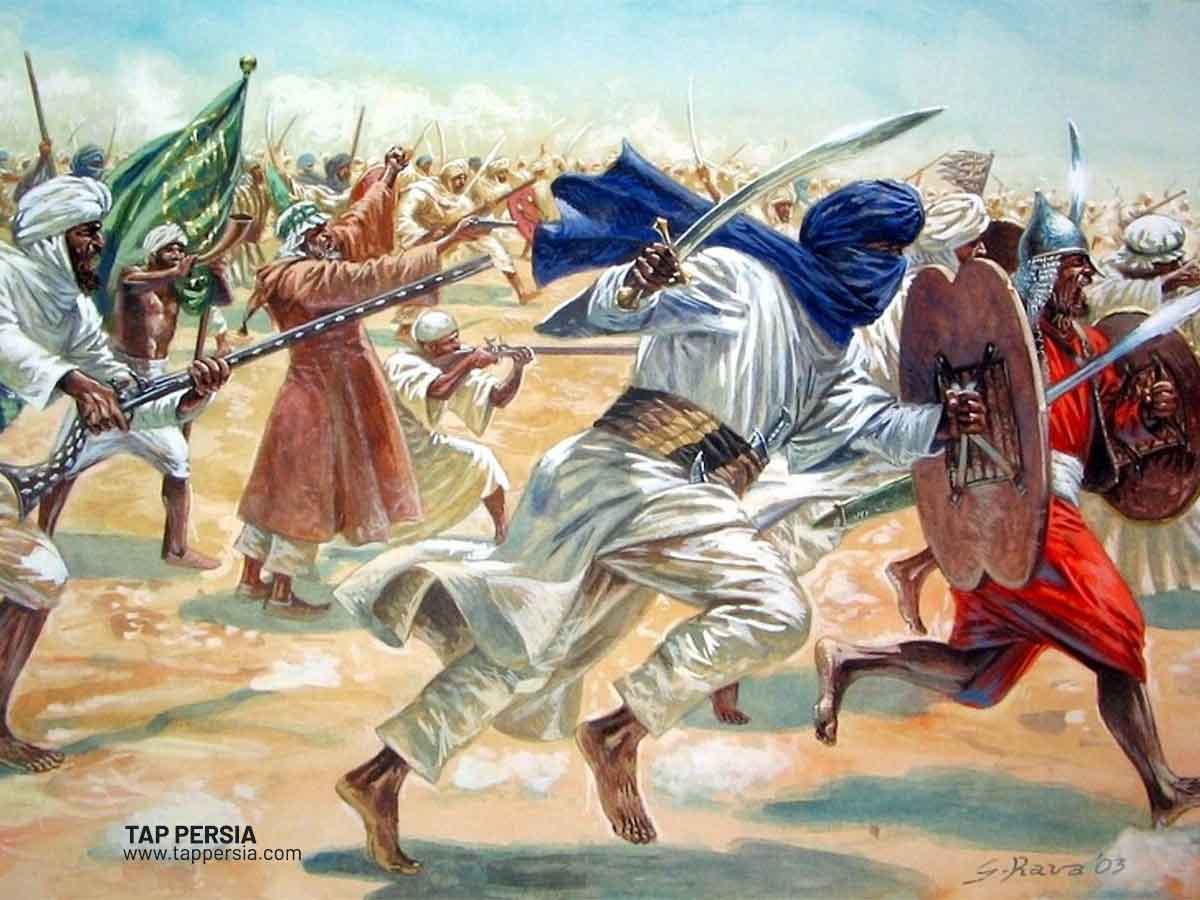

The Arab Conquest: The Introduction of Islam

Another important event in the history of Iran was the Arab conquest of Persia. Abu Bakr, the first Caliph of the Muslims and the first successor to Prophet Muhammad after his passing in 632 AD, made an effort to propagate Islam and subjugate all the adjacent lands to the Arabs. The second Muslim Caliph, Umar, launched an offensive against Persia. Yazdegerd III, the final Sassanid ruler, escaped to various parts of Iran where he was assassinated by a miller.

In 637, the Arabs took control of Ctesiphon, the Sassanid dynasty’s capital, and in a few subsequent years, they also took control of eastern Persia. The Umayyad dynasty, which was wholly Arabic in character, was created in Persia when the Sassanid Empire was overthrown in the Nahavand War in 641 AD. Because Islam was treated fairly by others and by them, the Persians eventually converted to Islam. The Arabs attempted to alter the Persian culture of the Iranians and imposed their own customs, traditions, habits, politics and laws on them.

They also declared Arabic to be the official language of the nation. Iranians never fully embraced the Arabic language and culture, although both Persians and Arabs acquired elements of one other’s customs and traditions. A new Islamic Persian culture was established as a result of the mixing of the two civilizations.

Samanid Dynasty: Preserving Persian Culture

The Samanid state, also known as the Samanian Empire, was a Persianate Sunni Muslim state of Iranian Dehqan descent. In its heyday, between the years 819 and 999, it was centered on Khorasan and Transoxiana, with Persia and Central Asia making up the bulk of its territory. The Samanid state was formed by Nuh, Ahmad, Yahya, and Ilyas. The Samanids’ feudal system was fully abolished in 892 when Ismail Samani brought the Samanid realm under one centralized authority.

The Samanids separated themselves from Abbasid rule during his reign as well. The Samanid Empire was a component of the Iranian Intermezzo, which witnessed the development of a Persianate identity and culture that incorporated Iranian language and customs into the Islamic world. The development of Turko-Persian culture was subsequently influenced by this. The Samanids supported the arts and attracted intellectuals like Rudaki, Avicenna and Ferdowsi, while also advancing science and literature.

In comparison to the Buyids and Saffarids, they did more to resuscitate the Persian language and culture while still using Arabic for academic pursuits in the sciences and religion. The Samanid rulers proclaimed in a well-known decree that here, in this area, the language is Persian, and the monarchs of this kingdom are Persian kings.

Seljuk Empire: The Turkic Influence in Iran

The upper middle ages saw a Sunni Muslim state based on Turko-Persia. In the eleventh century, a group of nomadic Turkish fighters known as the Seljuks emerged in the Middle East as defenders of the crumbling Abbasid Empire. They established the Seljuk Sultanate after 1037, which encompassed Iran, Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as Baghdad as its capital. The Seljuk Empire greatly ruled many lands. The territory of the empire in this part of the history of Iran spanned across the Hindu Kush in the east, Western Anatolia, the Levant in the west and Central Asia to the Persian Gulf in the south.

Tughril (990–1063) and his sibling Chaghri (990–1060) established the Seljuk Empire in 1037. From their native homelands near mainland Persia, the Seljuks went into Khorasan, then eastern Baghdad and eventually Anatolia. Following their victory at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the Seljuks went on to seize control of the majority of the remaining Anatolia from the Byzantine Empire. This served as one of the impetuses for the First Crusade (1095–1099). The Khwarazmian Empire replaced the Seljuk Empire in 1194 when it started to fall in the 1140s.

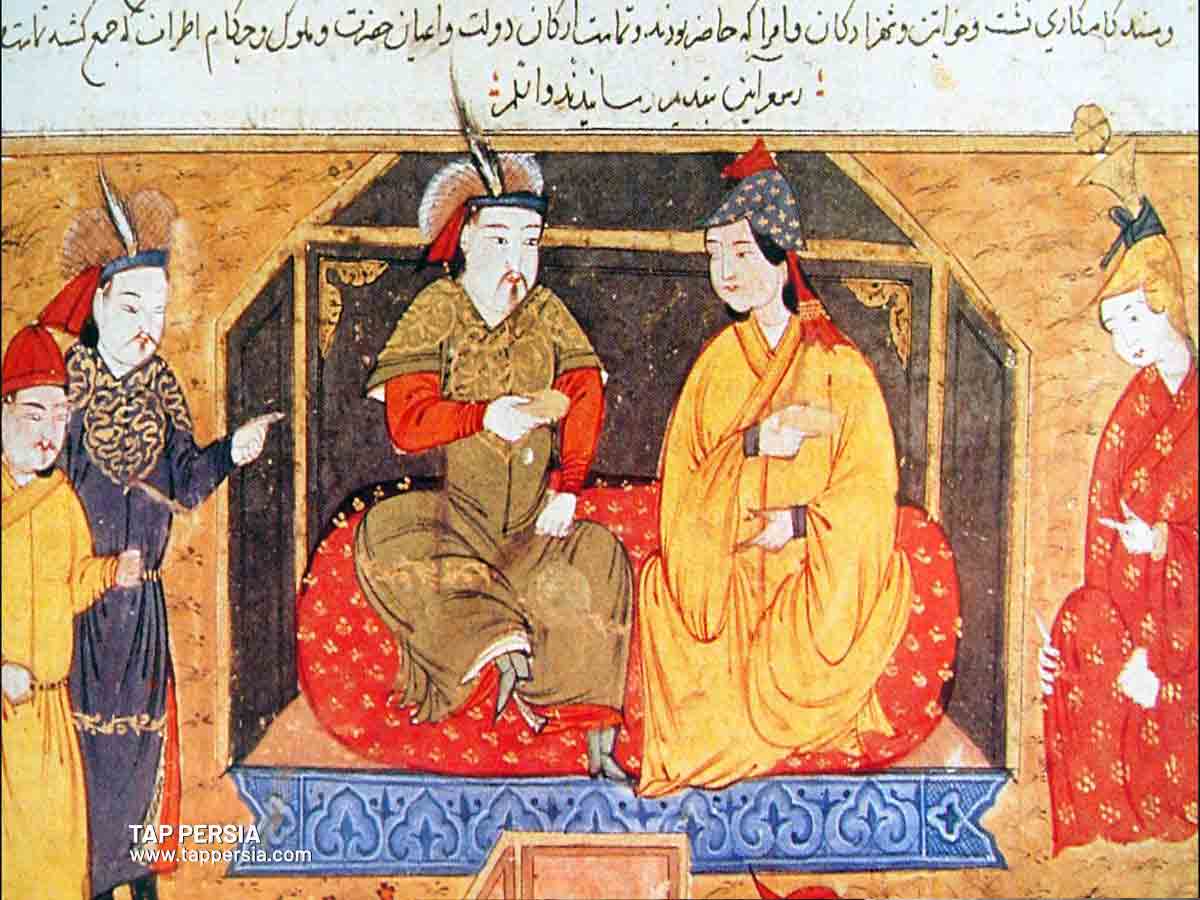

Ilkhanate: Mongol Invasions and Persian Renaissance

The Mongol Il-Khanid dynasty, also known as Il-Khan or Ilkhan, governed Iran from 1256 until 1335. Genghis Khan’s great-grandson Hülegü was tasked with conquering Iran by Möngke, the most powerful Mongol lord. Hülegü set off in 1253 and established the Il-Khanid dynasty in 1258.

After several centuries of fractured control, the Il-Khans strengthened their position in Iran and brought the area back together as a political and geographical entity. Mahmud Ghazan (1295–1304) lost all communication with the last remaining Mongol chieftains in China during the reign of the Il-Khanid Mahmud Ghazan (1295–1304). His rule coincided with an Iranian cultural renaissance during which Rashid al-Din and other academics flourished in this part of the history of Iran.

In 1310, Ghazan’s brother Ljeitü converted to Shiite Islam, leading to civil strife. Ab Saad, his son and successor, reverted to Sunni Islam, but factional conflicts and internal commotion continued. Without a successor, Ab Sa’d passed away, causing the dynasty’s continuity to break down. After 1353, numerous Il-Khanid rulers reigned over various areas of the previous dynasty’s domain.

Timurid Empire: Reviving Persian Art and Architecture

Ulugh Beg, one of the most notable Timurid rulers, was a grandson of Timur who emerged as a patron of arts and sciences, enhancing the empire’s reputation. Born in 1394 in Sultaniyeh (modern-day Iran), he ascended to power in Samarkand in 1447. Ulugh Beg was not merely a ruler, but also a great astronomer and mathematician. His observatory in Samarkand was one of the most advanced of its time. Scholars from around the Islamic world were drawn to his court, leading to a significant cultural and scientific flowering. Despite his military struggles, his reign symbolized a high point in Central Asian intellectual history.

Safavid Empire: The Golden Age of Iran

The Safavid dynasty (1501–1736), which governed Iran for about 200 years, is sometimes regarded as the start of the modern history of Iran. A significant contributor to the creation of a shared national identity among Iran’s numerous ethnic and linguistic groups was Safavid’s success in making Shiism the country’s official religion. Shi’ite Sufi organizations grew in strength during the 15th century as Shi’ism did as well. The Safavid Sufi dynasty descended from Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili, head of the Sufi order of ‘Safaviyeh,’ who progressively acquired control in the Azerbaijan region and the surrounding area, was credited with being the oldest Shi’ite Sufi order at this time. Until they entered the Iranian kingdom at the start of the 16th century, they supplied a monarchy-like structure. A significant turning point in the history of Iran was marked by the rise of the Safavid dynasty, which marked the end of centuries of foreign domination and the beginning of Iran’s reemergence as a strong, independent nation in the Islamic East.

Rise of the Safavids: Establishing Shia Islam

Iran (Persia), which had a predominance of Sunnis, became the spiritual center of Shia Islam as a result of the Safavid conversion of Iran to Shia Islam, a process of forcible conversion that occurred roughly during the 16th and 18th centuries. It is an important part of the history of Iran.

Shah Abbas I: Transforming Isfahan into a Cultural Capital

Shah Abbas I the Great (1587–1629) was the most powerful Safavid emperor, who assumed power at the age of 16. He began by taking on the Uzbeks and retaking Herat and Mashhad in 1598. By 1618, he had turned against the Ottomans and had retaken Baghdad, eastern Iraq, the Caucasian regions, and more. After disobeying his Georgian subjects, Abbas conducted a punitive expedition in his Georgian lands between 1616 and 1618. This campaign destroyed Kakheti and Tbilisi and took 130,000–200,000 Georgian prisoners to mainland Iran. The Ottomans were defeated in the 1603–1618 conflict by his new army, which had been strengthened by the arrival of Robert Shirley and his brothers.

In Bahrain (1602) and Hormuz (1622), Abbas I drove the Portuguese out with the help of his newly acquired troops. He strengthened his business ties with the Dutch East India Company and built solid ties with European royal dynasties. As a result, the Safavid dynasty was able to consolidate power and remove its reliance on the Qizilbash for military might. Along with its competitor the Ottoman Empire, the Safavid dynasty rose to prominence globally and fostered travel to Iran. In several Iranian towns, including Isfahan, Persian architecture once again thrived, giving rise to numerous new monuments.

Art and Architecture: Masterpieces of the Safavid Era

Since originality in all forms of artistic expression ceased towards the middle of the 17th century, the Safavid era also represents the final important advancement in Islamic art in Iran. Even when they lacked creativity rugs and gold, enamel and silver artifacts were nevertheless produced and displayed impressive technical skill. Many of the works of art produced during the time period are attributed to the Safavid Dynasty. The elegance we can today see in Iranian mosques was established via the arts and architecture. Calligraphy, mosaics, mirror artwork, and stucco are all included.

Cultural Exchange: Safavid Iran and Europe

A large coastline between India and Arabia gave the Safavid Empire a favorable geographic location for commerce. Safavid Empire raw silk and silk fabrics were a significant export. Additionally, during the contemporary era, Persian carpets were quite popular in Europe. According to research, the strengthening of ties between Iran and Europe during this time period also sparked various forms of cultural and artistic exchange, exposing Iranians to some of the Europeans’ cultural and artistic expressions in painting, music, and other areas. As a result, some changes in Iranian culture and art were subsequently made. The Europeans have been involved in these areas as well as scientific discussions, the translation of some literary works into European languages, the transfer of Iranian creative creations, and the representation of Iranian culture and way of life to the Europeans.

Qajar Dynasty: Transition and Modernization

Azerbaijan, which is now, used to be a part of Iran, and the Qajars were a Turkmen tribe that had ancestral lands there. The Qajar period saw a rapid development of Iran’s foreign commerce. We shall go into greater detail regarding the Qajar Dynasty and its impact on Iran’s sociopolitical environment during that part of the history of Iran.

Zand Dynasty: A Brief Interlude

Karim Khan Zand emerged as one of the main candidates for power after the death of the Afsharid emperor Nader Shah (1747). He had enough established his authority by 1750 to appoint himself vakil (regent) for the Safavid Esmail III. Karim Khan kept Esmail as a representative rather than claiming the title of Shahenshah (the “king of kings”). Karim Khan’s 30 years of benign reign in southern Iran provided a much-needed break from ongoing hostilities. He promoted agriculture and established trading ties with Britain. After his death in 1779, there were internal conflicts and succession issues.

Five Zand monarchs held short-lived reigns between 1779 and 1789. Asserting his authority as the new ruler of Zand in 1789, Lotf Ali Khan (reigned from 1789 to 1794) quickly put an end to a revolt headed by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar that had started after Karim Khan’s demise. Lotf Ali Khan was ultimately beaten and taken prisoner at Kerman in 1794 despite being outnumbered by the stronger Qajar army. The Zand dynasty was finally overthrown by him, and the Qajars dynasty took its place.

Qajar Dynasty: The Influence of European Powers

Agha Muhammad Khan’s 1786 proclamation of the Qajar dynasty marked the beginning of a time of relative stability in Iran that lasted through 1925. His two most important successors, Nasir al-Din Shah (1848-1896) and Fath ‘Ali Shah (1797-1834) oversaw the stabilization of Iran’s borders in accordance with their available boundaries and maintained a mindful harmony in the country’s affairs with the religious, administrative, and commercial authorities in addition to in relations with European powers on a worldwide basis.

One of the primary outcomes of Qajar’s foreign policy was an increase in contact between Europeans and the Iranians who hosted them, including diplomats, military men, technical and educational professionals, merchants, archaeologists, and curious travelers who spent extended amounts of time in Iran. As one of the major tenets of Iranian social culture, hospitality, entertainment and receptions played a significant role in official diplomacy as well as at private picnics and parties.

Constitutional Revolution: Democratic Transition in Iran

An “epoch-making event in the contemporary past of Persia” that led to the establishment of a parliament in Persia (Iran), was the Persian Constitutional Revolution occurred in 1905–1911. It was preceded by the Young Turks’ movement in 1908 and paved the way for discussion in a developing press and the modern period in Persia. The 1906 constitution was ratified by the monarch Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar. Mohammad Ali Shah, who had help from the British and Russians, replaced him and abrogated the constitution. The constitution was reinstated in 1909 as a result of a second attempt. The removal of the Second Majlis members from the parliament by Shah’s ministers and 12,000 Russian troops put an end to the revolution in December 1911.

Qajar Architecture and Art: Blending Modernity and Tradition

Iran’s Qajar dynasty produced works of art, architecture and other types of works of art between 1781 and 1925. An unintended consequence of the time of relative calm surrounding the rule of Agha Muhammad Khan and his heirs was the explosion of creative expression that took place throughout the dynasty. The representation of items, particularly by Qajar painters, reflects the time of realism in European painting. The architecture of earlier eras, particularly Safavid, is carried through into the Qajar period. Crescent-shaped and arc-shaped fenestrations above Orsi, Santouri, and springhouses are only a few of the architectural components and shapes that came into use during the Qajar period.

Contemporary Iran: A Nation of Contrasts

We are nearing the end of the historical dynasties of Iran. Here in this era after the Qajar Dynasty, we will see other hardships and turmoil again started by Reza Khan, otherwise known as Reza Shah. So, without further ado, we will talk about the last chapter of the history of Iran, contemporary Iran.

Pahlavi Dynasty: Reza Shah and Mohammad Reza Shah

Reza Khan assumed the throne when the last Qajar Shah was removed from power and began to rule as Reza Shah Pahlavi, establishing the final royal dynasty in Iran. Following this period and under Reza Shah’s rule, a number of reforms were implemented in an effort to build the framework for a modern state. Reza Shah had widespread popularity at first, but several of his actions—including stripping the Parliament of its real authority, stifling the press, and executing or banishing many of his former supporters—quickly created a great deal of unhappiness in the nation.

He supported Hitler’s Germany during World War II, which led to an Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. Reza Shah was banished to an island off the coast of Africa where he succumbed to his injuries shortly after being compelled to abdicate in favor of his son Mohammad Reza.

Shah Pahlavi was supported by Western countries including the U.S.A and the UK. Ahmad Reza Shah Pahlavi had to struggle to assert his authority over the vast nation. His most significant measures during his reign were a programme to combat illiteracy and land reform. The “White Revolution” programme included significant changes to the nation’s political system. The British oil business withdrew when the Majles enacted a statute, proposed by Dr. Mohammad Mosaddeq that nationalized Iranian oil shortly after the war. However, a coup orchestrated at an American-British initiative toppled this prosperous administration.

Islamic Revolution: The Development of the Islamic Republic

The goal of the Iranian Revolution was to depose Mohamed Reza Shah Pahlavi, who had ruled the nation since 1941. Although Iran (Persia) experienced moments of economic success during the Shah’s leadership, the government was essentially a dictatorship at home. The ecclesiastical and secular authorities in the nation clashed violently during the conclusion of Mohammad Reza Shah’s rule. Public unrest started when Ayatollah Khomeini was taken into custody. Force was used to put an end to the uprisings, and Ayatollah Khomeini was banished. The Shah left Iran fifteen days before Ayatollah Khomeini returned.

The administration led by Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiyar was unable to oversee the country because the Regency and Supreme Army Councils, which were set up to rule in the absence of the Shah, were unable to do so. More than a million Iranians showed up and displayed mass protests in Tehran to support Imam Khomeini. The Islamic Revolution and the ensuing national referendum heralded the founding of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Iran-Iraq War: A Decade of Struggle

Since September 22, 1980, till August 20, 1988, Iran and Iraq have been at war with one another. The conflict started when Saddam Hussein’s Iraq attacked Ayatollah Khomeini’s Iran in order to seize control of the Shatt al-Arab River, conquer the oil-rich province of Khuzestan and permanently degrade Iran’s armed forces. There was no definitive winner in the conflict, which resulted in a UN cease-fire. The war’s death toll was substantial yet unreliable. The majority of estimates place the overall death toll of soldiers around 500,000, with comparable figures for both sides. However, according to some reports, there were more than a million fatalities. Additionally, more than 100,000 people perished in the war, making it one of the most horrible events in the modern history of Iran.

Remnants of the Past: Architectural Marvels Across Iran

In this section, we will talk about the magnificent structures throughout the history of Iran that display the greatness of each era:

Ancient Persia: Cradle of Civilization

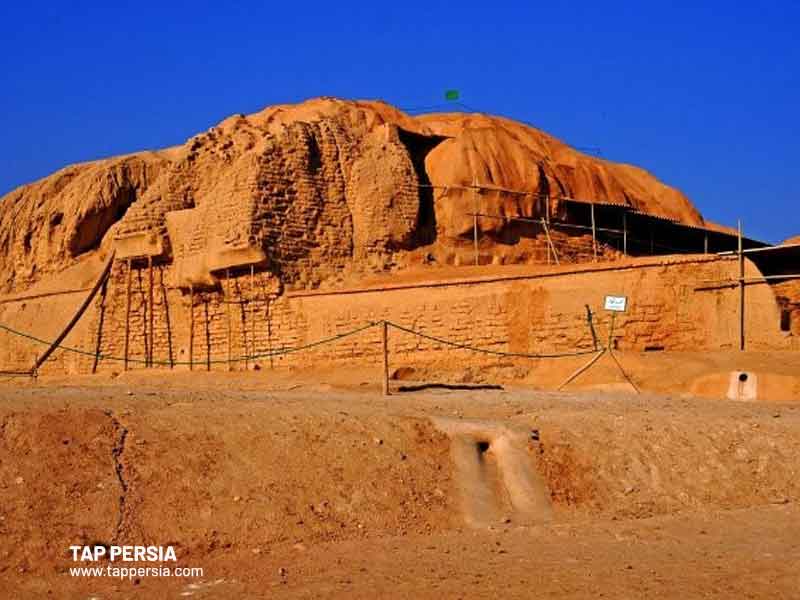

The remnants of Ancient Persia are so many that counting them may be a burden but we’ll name a few important ones. Persepolis which is the majestic Achaemenid capital, Chogha Zanbil which is a Mesopotamian ziggurat in Iran, and Pasargadae, the tomb of Cyrus the Great.

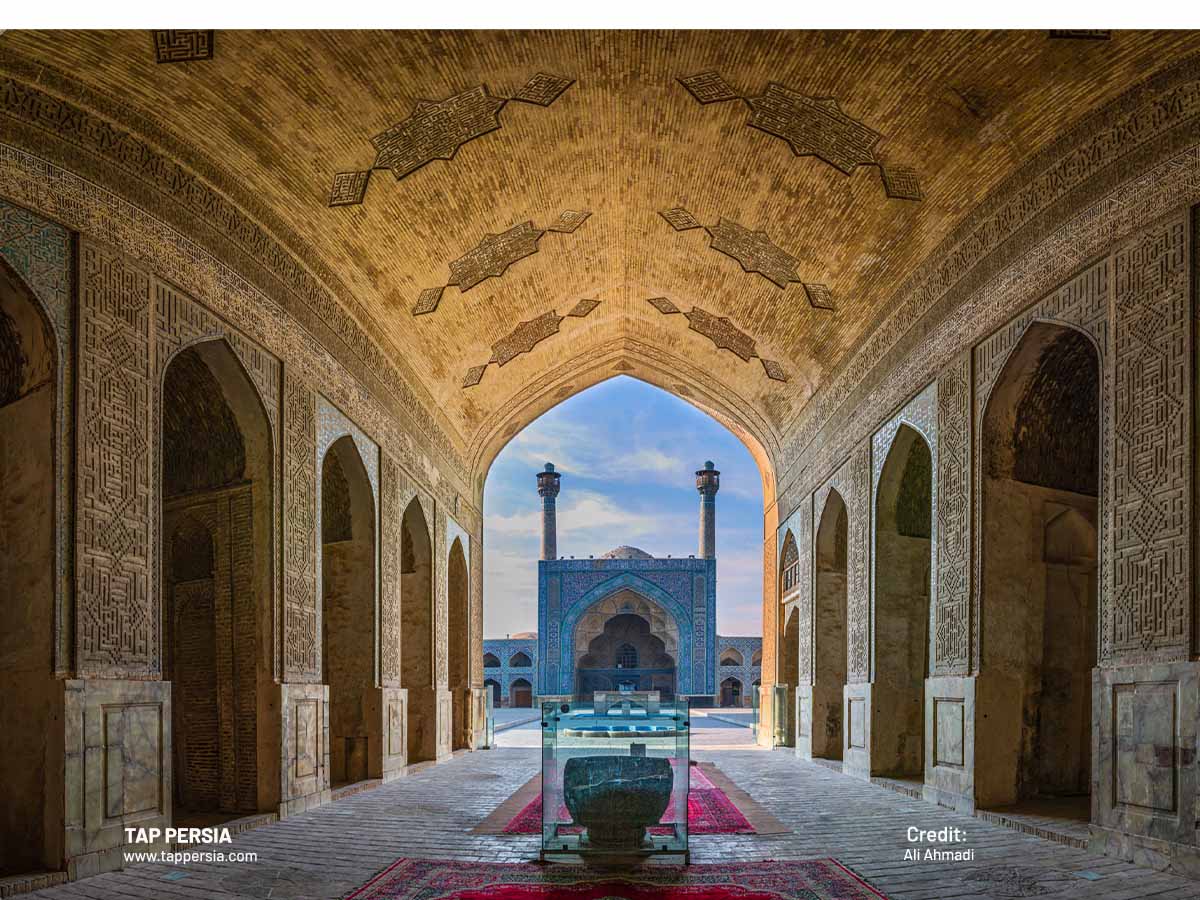

Medieval Iran: Shaping the Islamic Golden Age

Medieval Iran also has many remnants that we will name a few: The Jameh Mosque of Isfahan which is the Islamic architecture at its finest, Gonbad-e Qabus which is a towering masterpiece from the Samanid Dynasty, and the Friday mosque of Yazd which is a magnificent Seljuk influence.

Safavid Empire: The Golden Age of Iran

The Safavid Empire has a lot of historical structures that are noteworthy such as the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque which is a gem of Safavid architecture, the Ali Qapu Palace which is a symbol of royal grandeur in Isfahan, and Chehel Sotoun, a palace reflecting Persian elegance.

Qajar Dynasty: Transition and Modernization

Just like other dynasties, the Qajar Dynasty has many historical remnants of its past as well such as the Golestan Palace which is a glorious residence of Qajar kings, the Tabatabaei House which is an exquisite Qajar-era mansion, and Nasir al-Mulk Mosque which is a spectacular pink mosque.

Contemporary Iran: A Nation of Contrasts

Even in the modern era of Iran, we can see many structures that are counted as historical and will hopefully stand great as well in the future such as the Azadi Tower which is a modern icon of Tehran, Tabiat Bridge which is where nature and architecture meet, and Milad Tower, a fascinating multi-purpose tower.

Conclusion

There are many unique Iranian cultures and traditions that may be highly appealing and novel for visitors and cultural enthusiasts due to the incredibly rich culture and history of Iran. The nation has housed a number of emperors and dynasties, each of which left behind spectacular palaces, towns and monuments. Iran is an interesting place to go on an archaeological tour because of this. Therefore, you should select Iran the next time you want to go on a trip to a fascinating place with a rich history and culture and experience an incredible adventure for yourself.

Comment (0)